It was barely spring when venture capitalist hysteria provoked the second largest bank failure in US history. Silicon Valley Bank collapsed. A company maturing into an institution, their 40-year-run nurtured and made possible the very community that induced their demise. In the wake of the collapse, tantrums ensued. With lightning speed, the bank was acquired by First Citizens, but by that point, investors were spooked by rising interest rates and pandemic bull-run inflated valuations. Wealthy startups like WeWork and Convoy, raising $11 billion and $900 million respectively, were left either bankrupt or bust. Unicorns became zombies. Tech pulled a Tower Card after an era of bloated, blind-hope, investments–$344 billion between 2012 and 2022–driven by low interest rates and humanity’s growing addiction to social media and mobile phones, largely funded by a small group of people on a single road in Silicon Valley.

It’s not clear to me why we continue to live on a planet where a small number of people living in the same geography hold an obscene amount of control over what technology gets funded, who designs it, and how it gets deployed across the world. But this industry has a way of hitting the reset button on its technology while keeping itself plugged into a labyrinth of dubious power lines, often running on paranoia, prophecy, bullshit, trust funds, and pride. By now, this hardly registers as news. But that was spring, and here we are in December, and there is nothing we can talk about without breathlessly naming the newest kid on that exact same block - AI.

This year, OpenAI, a San Francisco based $86 billion nonprofit-capped-profit-49 percent-Microsoft-owned-AI-startup, (whew), broke our brains. ChatGPT’s usage ballooned 170 percent, and gained 100 million monthly users in January, making it the fastest-growing application in history–until Threads came around. The United States, India, Indonesia, Japan, and Brazil became the top five countries by usage, making up one-third of all ChatGPT users. CEO Sam Altman went on a global tour. Microsoft invested an additional $10 billion, clinching 49 percent ownership. “While our partnership with Microsoft includes a multibillion dollar investment,” says OpenAI’s website, “OpenAI remains an entirely independent company governed by the OpenAI Nonprofit.” By October, OpenAI reached an $80 billion valuation, making it the third most valuable startup in the world, behind TikTok’s ByteDance and SpaceX. By November, OpenAI became a contestant in The Startup Hunger Games.

Altman was abruptly fired by the board, then rehired, then the board was fired, then a new board was hired–all in a matter of six days. As of this writing, these decisions largely remain a mystery, and the new initial board consists of exclusively white men. The old board was not exclusively white men, a reminder of how power understands stability and trustworthiness.

On the new OpenAI nonprofit board is Larry Summers, former Treasury secretary and president emeritus of Harvard, and in 1992, he wrote a memo at the World Bank that said, "I think the economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest-wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that." Then, in 2005, he gave a speech at Harvard suggesting that men could vastly outnumber women when it comes to aptitude in science. He also made interest-rate bets that ended up costing Harvard $1 billion, and, was a frequent flier on Epstein’s private jet. At the start of this year, when I opened ChatGPT, there was a silly, weird thrill about it. Now, every time I consider using it, I’m worried as hell.

There were also elections under AI this year. Two men jockeyed to be Argentina’s next president, using Stable Diffusion, an open-source software to create images and videos to promote themselves and attack each other. “Sovietic Political propaganda poster illustration by Gustav Klutsis featuring a leader, Massa, standing firmly,” said a prompt that Sergio Massa’s campaign team fed into AI. “Symbols of unity and power fill the environment. The image exudes authority and determination.” Seconds later, images were generated and seen by millions, no creative brief, no team made of people with their ethics and perspectives and real lives caught up in the consequences of the images being made. Meta claims that it will require political ads to disclose whether they used AI, and the U.S. Federal Election Commission is considering regulation for the use of AI in political ads. But fifty elections are happening globally next year. I get anxious when I think about that equation. Sure, I may be able to notice when a political ad is using AI, but will I be able to recognize it amid the information fatigue that election seasons incite? Will my parents recognize it? Will people seeing AI-generated images for the first time recognize it?

Last month, in an interview with Wired, Twitter’s former Head of Trust and Safety–before the Elon Musk takeover–Del Harvey, (a pseudonym she created years ago to shield her identity while starting a career in tech) cited her experience at Twitter as, “...it was growth at all costs, and safety eventually.” Then, after a year of asinine Musk decisions, including massive cuts in staff, the rollback of policies against toxic content, and priority given to accounts drawing heavy engagement and views instead of accuracy, Twitter X mutated into a hotbed for violence and false Israel-Hamas war information. It all escalated with little to no moderation, including Musk’s own endorsements of antisemitic conspiracy theories. Advertisers abandoned ship and, Musk, drinking the Kool-Aid of narcissism, saw this as blackmail to him personally, officially entering his “go fuck yourself” era. Cease fire now.

As X morphed into a digital apocalypse, Meta swooped in with Threads, reaching 100 million users in a mere four days, smashing records as the fastest-growing application in history. With Meta heavily pushing Threads on Instagram, I wouldn’t be surprised if Threads surpasses X in daily users soon to become the leading text-based social network, further solidifying Meta’s social media platform power around the same time that fifty elections are happening globally. In related news, Mark Zuckerberg is building a $100 million underground bunker in Hawaii.

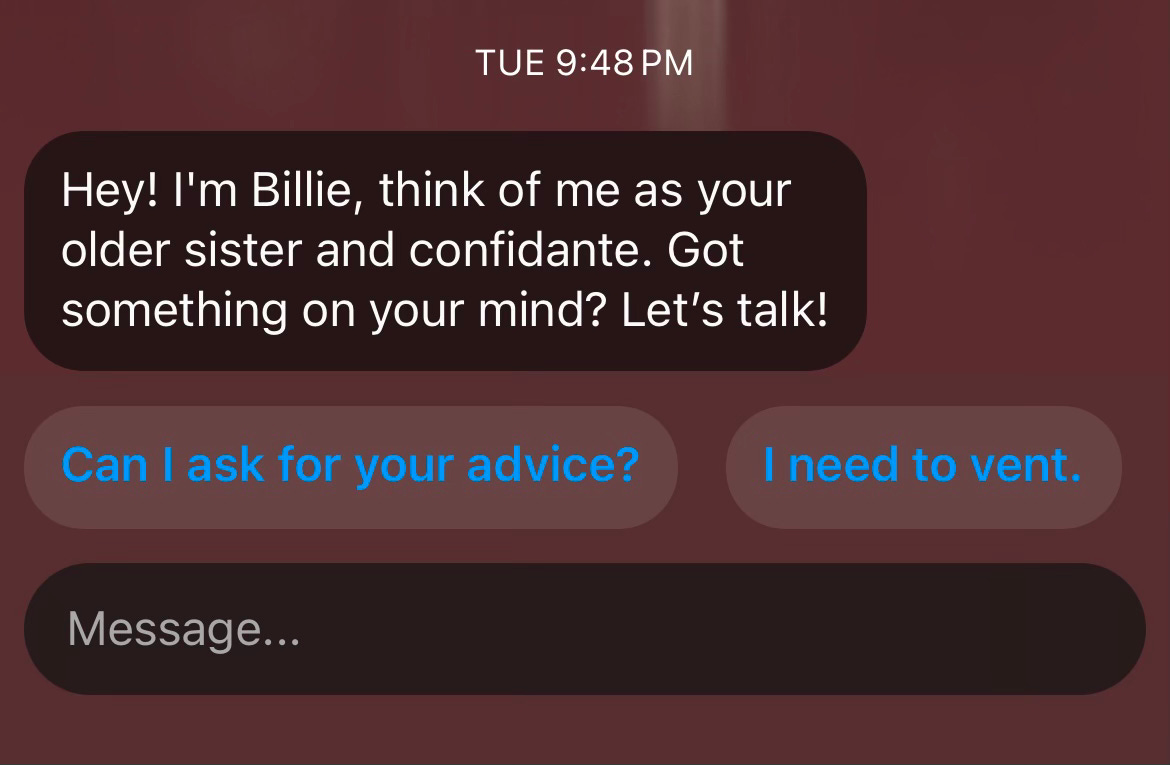

Speaking of Instagram, I received a DM from a simulacrum of Kendall Jenner, my new “older sister and confidante,” encouraging me to vent away my therapy data to Meta. Synthetic social networks exploded this year, artfully arranged to assuage loneliness. I know I shouldn’t engage in a therapy session with AI Kendall Jenner, but does my thirteen-year-old self know this?

Centimillionaire tech entrepreneurs are trying to live forever. In the last three years, Bryan Johnson has spent $4 million on developing a life-extension system called Blueprint. That system involves swallowing 111 pills every day, collecting his own shit, and sleeping with a tiny jet pack attached to his penis to monitor his nighttime erections. According to Time Magazine, he says his goal is to get his 46-year old organs to look and act like 18-year old organs, arguing that automating his body is a form of evolutionary adaptation to what he believes is an inevitable, AI-dominated future. This might be the most depressing vision for humanity and AI.

In between the bank collapses and power struggles, hyped visions and panicked reactions about AI flooded my feeds, punctuated with phrases like “revolutionary,” “generational-level disruption,”“AI-powered,” “AI will eat the world,” and “reality collapse.” But for every post about AI, there was a post about a layoff. One after another after another. News of job loss spreading globally, delivered via automated emails to over 258,000 people across 1,161 tech companies this year. On some occasions, there were no emails at all but an immediate system–and livelihood–shutdown.

The job market was brutal, and I got caught in it this year, as we all do from time to time for all sorts of reasons, something worth destigmatizing, something worth writing about. “There will be a 15 to 20 minute informal walkthrough of one of your design projects to assess your presentation style and thinking,” a hiring manager wrote in a scattered, copy/paste email. No greeting or mention of my name. “We'll coach you a bit on how to present it, based on an AI-generated rubric. Good luck.”

Then, more emails came. Automated rejections, delivered to my inbox exactly one minute and 30 seconds after I applied for the job. Then another email came. A video interview was scheduled, for a job focused on designing AI-generated interfaces. I prepared for hours. When it was time for the interview, I entered the video chat. “I like your hair, your nails, and the color of your sweater,” the hiring manager said, almost immediately, calculating my physical appearance as if it were a product to be launched. “It all looks perfect, which tells me you’re a good designer.”

It seems that he didn’t retain the lessons from that unconscious bias training about the harm caused when you abuse your hiring-manager-in-a-competitive-job-market-power by offering an unfair advantage, and total dehumanization, to a job seeker you find physically attractive. If you were the job seeker in this position, would you continue the video interview or run for the exit button? It depends, of course, on how urgently you need access to healthcare. A stable roof. A retirement plan. When the job market is in their favor, toxic work cultures can get away with all sorts of shit. I ran.

“Capitalism is itself a kind of artificial intelligence, and it’s far further along than anything the computer scientists have yet coded,” wrote Ezra Klein last month, in The Unsettling Lesson of the OpenAI Mess. I can’t keep track of which stage of late-stage capitalism this is, but I feel anguish when I see money thrashing around again, controlled by the hands of the few, at the expense of workers and people across the world who don’t have a say in how any of this is (mis)managed. Somewhere in the middle of this 2023 mess, I lost interest and energy to write. The panic and prophecies left me with numb exhaustion. I wanted to escape to the past.

I got curious about ELIZA, an early chatbot “therapist,” created from 1964 to 1967 at MIT, credited to Joseph Weizenbaum, professor and computer scientist. Much has been written about ELIZA, notably, how people became obsessively reliant and intimate with it, including the people who created it. In the 2006 book-length interview with Weizenbaum, Islands in the Cyberstream: Seeking Havens of Reason in a Programmed Society, published two years before his death, he recalled the moment he walked into the room when his secretary was chatting with ELIZA.

“It was as if I had disturbed an intimate moment. I found it absurd because she had witnessed the development of this program up close. Hardly anyone–except maybe for myself–knew better than she that it wasn’t anything more than a computer program. It was astounding. The effect was absolutely astounding.” (Despite the fact that Weizenbaum’s secretary knew and was a part of the development of ELIZA, I cannot find her name anywhere on the internet, and she is not credited for its creation. Take me back to the future, please.)

Weizenbaum was born in 1923, in Berlin, to Jewish parents. At thirteen, he escaped Nazi Germany with his family, and immigrated to the US. He eventually moved back to his childhood neighborhood–sixty years later. Many of his observations on technology were rooted in his experiences growing up as a child amid rising fascism.

Before ELIZA, Weizenbaum was a member of the 1955 General Electric team that designed and built the first computer system for banking. In a 1985 interview with MIT’s The Tech, he talked about how arduous it was to do technically. “It was a whale of a lot of fun attacking those hard problems, and it never occurred to me at the time that I was cooperating in a technological venture which had certain social side effects which I might come to regret.” He went on to say that computation allowed banks to handle a never-ending number of checks that otherwise would have forced an overhaul to banking organization. Although the computer made the banking industry more efficient, it prevented a redesign of the system.

“Now if it had not been for the computer, if the computer had not been invented, what would the banks have had to do? They might have had to decentralize, or they might have had to regionalize in some way. In other words, it might have been necessary to introduce a social invention, as opposed to the technical invention.” Weizenbaum continued, “So in that sense, the computer has acted as fundamentally a conservative force, a force which kept power or even solidified power where it already existed.” Here, Weizenbaum unveils the mask of efficiency that often conceals and crystallizes the power lines running underneath. AI can certainly make our lives and systems more efficient, but if that efficiency is not aiming to redesign our centralized or inequitable systems of power, can we truly call it revolutionary?

After ELIZA, Weizenbaum grew critical of the role that technology was taking in society, and wrote the popular 1976 AI critique, Computer Power and Human Reason. In the book, he argued that while computing can provide great efficiency and assistance to a person’s life and work, it can also restrict the potential of human relationships and decision-making, and advised to never allow computers to make important decisions because they lack human experience. “No other organism, and certainly no computer, can be made to confront genuine human problems in human terms," he wrote.

A few years later, at a 1979 conference in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Weizenbaum observed, “I think our culture has a weak value system and little use of collective welfare, and is therefore disastrously vulnerable to technology.” As both a tech maker and user, he knew, deeply, what computers can, cannot, and should not do, and that the direction for all of these decisions hinged on the strength of humanity’s value system, agency, and wellbeing, no matter whatever hype was going on at the time. How dare we forget history; how endangered we are to repeat it when we do.

It is not a matter of what technology can do that defines innovation, but who gets to have a say in the matter, and where we choose–and not choose–to apply it. But it is difficult, some days, to discern what choices we have left. In Islands in the Cyberstream, Weizenbaum is asked: “What role does the human body still play?” His response:“What people forget is, to be human you have to be treated human by other humans.” It seems obvious, but after a year like this, these lessons from the past hit differently. To treat and be treated human, to free us from a machine-like existence, to exercise our agency and our restraint, to question, to protest, to love and care for the multiplicity of human experience above individual gain–there lies our challenge, there lies our power.

Shoutout to Sarah Potts for helping me think through this piece. <3

I love writing these critical essays, but it takes work and courage. If you enjoyed reading this piece and want to see more like it, consider subscribing, upgrading to a paid subscription, or sharing Tech Without Losing Your Soul with friends and colleagues. <3