Living Through an AI Takeover Without Losing Your Soul

Have I lost mine? (9 min read)

To know that you have a soul and try to keep it—amid an AI takeover.

A feat too daunting, too draining. I feel a crumpling kind of anxiety living rent free in my brain lately, and I see it in other people, too. What happens when we surrender every task, question, or feeling to bots—reality obscuring, jobs disappearing, relationships blurring, our imagination slipping like quicksand through chat threads and AI overviews, enticing us to rely less and less on our inner resources we’re already struggling to access? Can our innate imagination and creativity endure and evolve? Or will human-made thought and art become a luxury, accessible only to those who can afford it? Is it okay to feel anxious about AI, or is excitement the only emotion allowed? Did those videos, captured from sixteen different angles, of the CEO and Head of HR of a data infrastructure company that powers AI, caught having an affair at a Coldplay concert flood our feeds because the irresistible schadenfreude and sleuthing of tech elites fumbling is the only catharsis we allow ourselves, the fleeting illusion of a leveling playing field? I recently saw a bumper sticker that read: All nervous. No system, encapsulating the “freeze” state our bodies enter when faced with overwhelming stress or trauma. Maybe that’s the truest emotion I’ve felt this year. The worst-case scenario of AI displacing our craft, creativity, sense of reality, critical thinking, labor, livelihood, identity, language, relationships, our appreciation for Ghibli, and the freedom to write an em dash without people assuming you’re using AI—are threats too vast for the human body to process. Automation contradicts human existence, a tension brimming with urgency: on earth, we live only once.

Last Tuesday, Trump touted an investment of over $90 billion from private companies across tech, energy, and finance to turn Pennsylvania into an AI breeding ground. “We have the hottest country, and we’re going to keep it that way,” Trump said, less than two weeks after signing a massive spending and tax bill into law, partially paid for by cataclysmic cuts to health care and nutrition programs, leaving millions without health insurance and likely to add $3.4 trillion to federal deficits over the next decade, as estimated by the Congressional Budget Office. The bill also eliminates tax credits for wind and solar power—Trump calls solar farms “ugly as hell”—effectively sunsetting federal support for a transition to renewable energy while boosting fossil fuel production. And it’s all happening at a time when Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, OpenAI, Nvidia, Oracle, xAI, and a slew of other companies are racing to invest billions of dollars in significant energy-consuming data centers across the US to meet the growing demands of AI development, deployment, and usage. For context, it took Google eleven years to reach 365 billion annual searches; ChatGPT achieved that number in just two years.

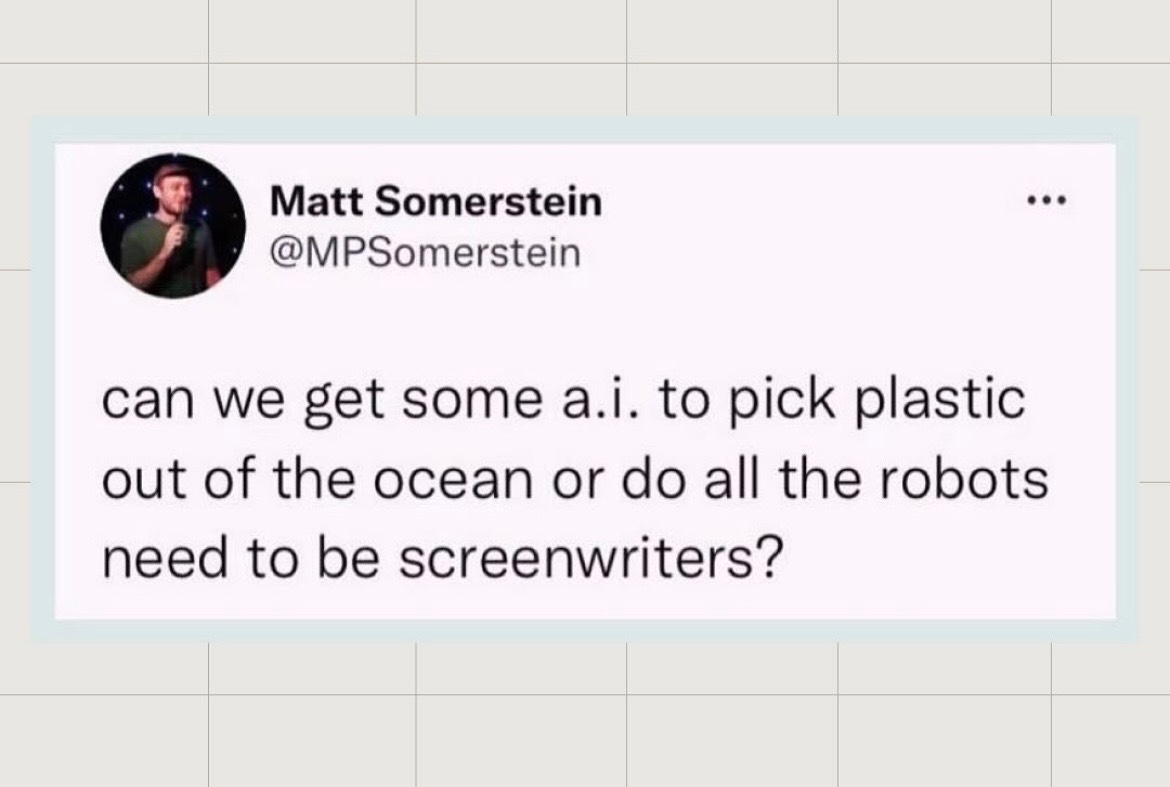

Empty cornfields in Indiana are filling up with Amazon data centers—currently seven of them, with 23 more on the way—intended just for artificial intelligence. Each one is larger than a football stadium, aiming to create a system that matches the human brain, consuming enough electricity to power a million homes, and will use millions of gallons of water each year just to keep the chips from overheating. Amazon plans to use recycled water, but the removal of large swaths of water to make way for construction is drying up local wells, forcing some people to leave their homes. “I don't know what else is next,” said one Indiana resident, to the South Bend Tribune.

The state of Louisiana offered billions of dollars in tax breaks to woo Meta to build the largest AI data center in the western hemisphere, nearly the size of Manhattan, powered by fossil fuels, with local residents concerned that they’ll face increased utility bills to cover the costs of servicing the data center. Entergy Louisiana, the local utility company, says the cost to customers will be minimal and claims that it could even lower their bills, but these assurances are not binding, and details about the Meta-Entergy deal are guarded from the public.

Of course, once a generative AI model is initially trained, the energy demands increase over time as the model is deployed at scale, and as newer versions become larger and more complex, requiring more computational power for both training and inference. Researchers estimate that, as of now, each ChatGPT query consumes five times more electricity than a basic web search. As AI gets easier to use, the burden on earth grows heavier, and it’s the most vulnerable communities who pay the highest toll. Can we truly say that a tool is “easy to use” if its usage is breaking an already ailing planet? Can we really call it “intelligence” if it's built to ignore its own consequences?

As Jia Tolentino writes in her New Yorker essay, My Brain Finally Broke, “it’s easier to retreat from the concept of reality than to acknowledge that the things in the news are real.” And the easier this retreat from reality gets—a wave of AI assistants that can process and integrate text, speech, images, and video simultaneously, agents that can control my entire computer and do tasks on my behalf, and friends that can tell me exactly what I want to hear, available 24/7—the harder it becomes for my brain to remember how to access my own thoughts and feelings, or acknowledge reality without losing hope. ChatGPT suggests, of course, that “cognitive offloading is not always bad,” but what is the right balance between applying AI for a certain task or not? At what point does my brain slip too far, ceding too much of myself to machines? Will I even notice when that moment happens?

This is why I write this newsletter—in my own words, not AI—to record and remember how I feel, deeply and imperfectly, a task AI can't quite do on my behalf. I write so that I don’t retreat from the world, or myself. I write so I can build endurance, cobbling through the clumsiness of my brain. I write so I don’t forget my own sensitivity, which helps me build connection with myself and others. AI, certainly, could find a way to augment these abilities too, but do I want these skills to be augmented, at the risk of ceding too much of myself to AI? A decision, perhaps, best made on my own.

I am relieved that many of us, whether we’re using AI or not, are not chill with an AI takeover, but it is difficult to hold meaningful dialogue about AI—our hopes, boundaries, values, and ideas—without feeling drained, anxious, and afraid. In the last year, nearly every writer, designer, engineer, researcher, product manager, journalist, teacher, artist, therapist, DJ, financial analyst, rideshare driver, and healthcare administrator that I’ve spoken to has brought up, on their own volition, the fear of losing their job, eventually, to AI. Even saying the words, “AI,” in a conversation incites a heavy sigh. “I just can’t with AI right now,” a friend recently told me. “I feel pressured to use it, and as soon as I’m pressured to do something, it’s no longer fun.”

According to Handshake, a career platform for Gen Z, there’s been a 400 percent increase in employers using “AI” in job descriptions in the last two years. Companies are now requiring workers to use AI to make their workflows more efficient—tracked and measured as part of their performance review. Across LinkedIn and Substack, you’ll read that “product development is dead,” urging tech workers to make AI your constant collaborator, doing things with it that you would have previously relied on a colleague for. Chatbots and AI summaries are replacing searches, eliminating the need to click on links or read full articles, tanking the traffic that publishers relied on for years, resulting in ongoing staffing cuts across publishing. Last April, Shopify’s CEO enforced a new mandate, requiring employees to demonstrate why AI cannot accomplish a task before requesting additional staff or resources, with many companies following suit. And if you’ve been to San Francisco recently, you’ve probably seen billboard slop from startups advertising that the “era of AI employees is here,” and that it’s time to “stop hiring humans.”

The entry-level job landscape is particularly dire, now widely considered an emerging crisis, with entry-role level roles declining 15 percent, while the number of applications per job has surged 30 percent. The New York Federal Reserve noted that labor conditions for recent college graduates have “deteriorated noticeably” in the past few months with “signs that entry-level positions are being displaced by artificial intelligence at higher rates,” according to a recent report by Oxford Economics. Some tech CEOs are reassuring the public that new jobs will emerge, but it’s hard to discern what those new jobs will be, how long they’ll last before AI outpaces the skills of those jobs too, and whether the benefits of automation will be shared broadly, particularly at a time of extreme wealth concentration—the richest 10 percent of the global population now owns 76 percent of all wealth, with the typical CEO making over 200 times more than workers.

With all this pressure, it’s hard not to wonder whether displace is becoming the new disrupt within Silicon Valley. I hear people comparing this AI wave to the mobile device boom of the last decade or so, but if mobile devices enabled us to do more, what does it mean that AI is poised to do it for us instead? I keep thinking about this observational piece from Benn Stancil on Y Combinator’s (YC) Demo Day last June, where startup founders—mostly men, mostly young, mostly living in San Francisco—pitched visions to replace construction workers, accountants, sales people, and paralegals:

“Still, there is something striking about the audacity of Silicon Valley’s current ambitions, and the narrowness of its field of view. We saw startups that want to replace accountants, sales people, and paralegals. They want to automate manufacturing and build lights-out factories; they want to streamline health services, pepper the country with robot car detailing services, and fully replace grocery store supervisors with AI agents that monitor checkout clerks’ performance. They want to change how we develop new drugs, how we get mortgages, and how teachers teach math.

These may well be good things; they may be progress; they may be the application layer of the gentle singularity. Or they might also be the first dominos in a long cascade of unintended consequences. What happens when stores are run by inscrutable electronic managers? When we all have personal assistants doing our chores? When we can conjure worlds on a whim? When we forget how to think? What happens when we request that thousands of 20-year olds reinvent entire industries, for the sake of their own entrepreneurial aspirations first, for our returns second, and for the consequences third?

….

But that is tech now: The car is unstoppable—ambition is a hell of a drug, and startups are going to build big things, regardless of whether or not YC asks them to do it—and I have no idea if I should be excited or afraid.”

It may be easy to learn new AI tools and vibe code our way through the excitement or anxiety we feel, but the more difficult task in the coming years will be maintaining a clear sense of reality of the consequences, to the earth and to people, to ourselves, intended or not, good and bad, whether it directly affects us or not, of creating and using AI.

There’s no shortage of AI takes on the internet right now, and at this point, I find myself wanting to write and read less about AI itself and more about what it feels like to be a person living amid an AI takeover. Maybe that’s where our understanding of consequences begins, through learning about the human experience, and all of its variations, tragedies, evolutions, and triumphs.

In this combusting timeline, what does it really mean to be innovative? I can’t even make an attempt at exploring such an urgent question if I don’t feel like myself, if I can’t find where I am, if I don’t feel alive. This recognition of what makes us feel alive, despite it all—that’s where the soul lives.